As I mentioned in my previous post, for my latest game design prototyping challenge, I decided to design a secret bonus level for Super Mario RPG. My goal in designing the stage was to create a fun and engaging experience that adapts the fun of a theme park experience into the Super Mario RPG universe. The allure of the stage is solving the mystery of the mysterious toymaker clown Karakas, whose funhouse factory has allegedly been abandoned. The factory has been locked, however, and there are four keys spread out throughout the amusement park that are used to unlock it, so the quest begins with a scavenger hunt throughout the amusement park to find the keys. Once the players find the keys, they can open up the factory and explore it, solving puzzles and fighting enemies along the way. They eventually reach the top of the dungeon to discover a closed jack-in-the-box. When they go to leave, however, Karakas springs out of the box and drags the players inside. He reveals his scheme to turn them all into toys and keep them in his lair forever, and a boss fight ensues. Once the players defeat Karakas, they are rewarded with exceptional weapons to aid them with the final few levels of the game.

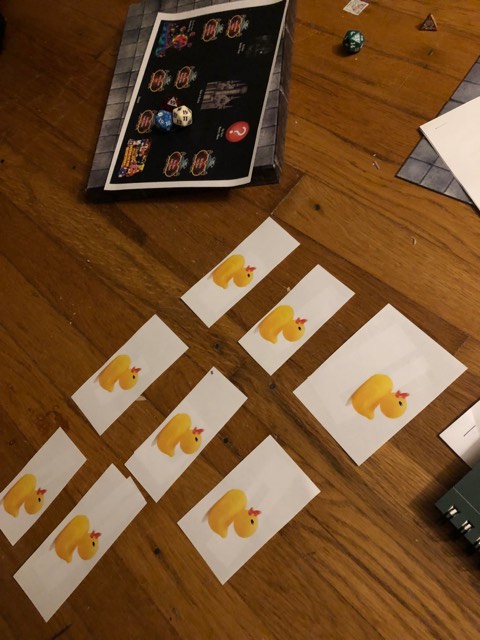

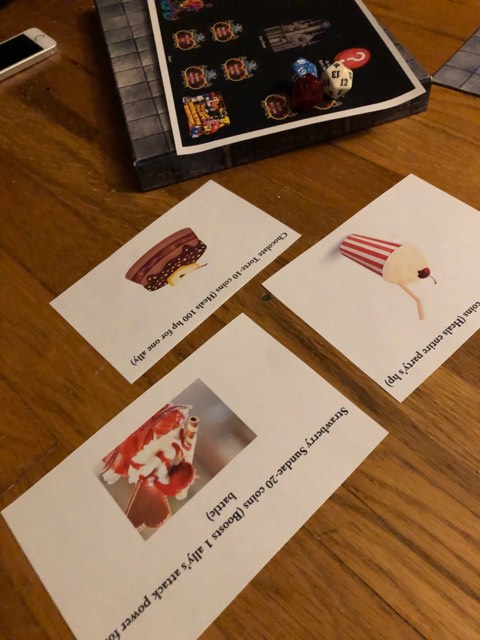

This time around, my process was focused on playtesting and iteration. I went through a very quick process, where I would test and then iterate and repeat the process, allowing myself to make lots of improvements and changes over a relatively short amount of time. The big difference with testing this time around was that I had more polished playtest materials, as can be seen below:

Players appreciated these new materials and were more able to become fully immersed in the game world. They also allowed me to cover more ground and get through more of the adventure in individual playtests because less time was put into verbal descriptions and scene setting, as much of what the players needed was right in front of them. For both of these reasons I will make the case that using more visual materials helps greatly with playtesting, because they allow one to skip past the clarifying questions and confusion about the game world and get to high level issues like design and narrative.

Now I won’t say that this process was easy. I easily spent over 20 hours preparing all of the playtest materials and organizing everything, and even then I still wasn’t able to implement everything that I wanted to. But with all of that being said, the payoff when it came to playtesting made it all worth it. Playtesters said that they felt as immersed in this experience as they ever have in a tabletop adventure, and they could actually picture this exact location in Super Mario RPG. In hearing that, I felt that I was successful in both my role as a designer and a playtest facilitator.

During this rapid iteration process, I placed particular emphasis on taking lots of pictures, and part of that was putting myself in the mindset of a photographer. During the action scenes and the exploration of the park, I made it my main objective to take pictures. Normally my emphasis would be on note-taking, but my thought was that if my pictures would good enough and if I took them consistently, that I could extract a lot of the information that I needed from the photographs. Anything that couldn’t be taken from them I decided I could get at the end of the playtest sessions.

For the end of playtest survey, I kept the structure fairly modular, with a set of core questions that I could ask while at the same time recognizing that they may have to be tweaked or changed based on what happened during the playtest. I also recognized that player actions may answer some of them as well, or that player actions would likely inspire new questions. The core list of questions are listed below:

1.) What did you find most fun about this level?

2.) What did you like least about this level?

3.) What is one thing you would change about this level?

4.) Would you go out of your way to play this level?

5.) Is there anything you would add to the level to make it better?

6.) Did you feel that the level was too hard or too easy?

7.) Did this adventure feel like a Mario adventure? Did you feel like you were playing as Mario and friends?

For each playtest this list changed, and since these were questions that I was asking the players in a one-on-one setting, and not a written form that I gave out, it contained a level of modularity that allowed for me to get the most useful information out of each session.

Overall, I feel that the rapid prototyping and playtesting method was very useful, and it allowed for me to design more quickly, efficiently, and effectively over a short period of time, taking what would normally be a multi-week or month process and condescending down into a single week. its undoubtedly a lot of work, but for me it enhanced my work and gave me better, more useful information from playtesting.